Will the Syrian revolution opt for a civic or Islamic state?

As a result of the repeated attempts to dress the Syrian revolution up with the turban of Islamism and hurl it into a sectarian debate, a political confusion has surfaced that weighs heavily on the minds of opposition activists. This debate revolves around the role of Islamic parties, which are represented by the Muslim Brotherhood, the impact they will have on revolutionary action and their future in the post-Assad period.

The Syrian opposition is still going back and forth between secularism and political Islam as it tries to assume a middle position between the two, especially after the victory of Islamic movements in legislative elections in Egypt, Tunisia and Morocco. If we examine the results of these elections, we will find that Islamists rode the tide of democracy in order to assume power.

Even though these parties took to the streets then won the ballots democratically, they have tried, on certain occasions, to set democracy aside. Democracy necessitates following the principles of the civic state and guaranteeing the freedom of expression, something that Islamic movements have failed to exhibit, as shown by the developments of the revolution in Tunisia and Egypt. The Salafists in Tunisia, for example, have tried to segregate male and female university students, in addition to banning women from teaching men. In Egypt, there were calls for starting a “committee to enjoin promote and prohibit evil” and to force women to stay at home. As a result of the rising popularity of political Islam in the countries that witnessed the Arab Spring, there was fear in Syria that Islamic parties could accede to power in the event of the fall of the current regime, which could be followed by the Islamisation of the state and the politicisation of religion.

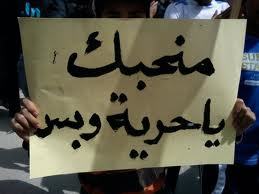

Islamic discourse in the context of the Syrian revolution was most obvious in the calls to name one of the Friday demonstrations, “the Friday of Jihad” or “the Friday of Islamic Wrath”’, which aroused a lot of controversy between different segments of the Syrian opposition. The debate revolved around the extent of the influence that Islamic movements have on revolutionary action. Many intellectuals and activists expressed their views through social media websites, refusing such names on the grounds that they only relate to certain groups of the Syrian people. There were calls, on the other hand, to adopt a name such as “the Friday of Civic Pluralism”, to which all Syrians could relate, and to relinquish any reference to “jihad”. This pushed the administrators of the Facebook page “the Syrian Revolution against Bashar al-Assad” to issue a clarification about the idea of jihad. Abandoning the name “Friday of Jihad” was the clearest proof so far that the Syrian people refuse to adopt a populist religious discourse.

It has become obvious that a struggle is tearing the opposition apart over the political future of the country. There is no doubt that the solution will eventually be a civic state that establishes a balance between the different sectarian groups, because Syria is not like the other countries that witnessed the Arab Spring. There is, indeed, an Islamic movement in Syria that has a political role, but it only represents one element of the wider political spectrum. The political behaviour of the Islamic movement, led by the Muslim Brotherhood, which dominates the Syrian National Council, is still moderate and far from Salafist or other fanatical trends.

Revolutionaries have also demonstrated a depth of perception and appear to be opting for a civic state in the post-Assad era, since the popular movement is still dominated by the National Coordination Committee of the Forces of Democratic Change. The committee has among its members young intellectuals and activists in public affairs, politicians and legal experts, representatives of secular, nationalist and Marxist parties, as well as moderate Islamic parties and 11 nationalist or secular Kurdish parties. Several civil political movements have also been formed. These include the Syrian Movement of State Building, the Coalition of Syrian Left, the Pulse Association for Syrian Civil Youth, Together Movement and the League of Syrian Secularists. This means that the popular movement has members from different political and intellectual backgrounds. In other words, Syria has a rainbow of parties, part of which are Islamic parties. It is enough to remember some of the slogans repeated by demonstrators to see how committed the revolution is to being civil, “Neither Salafists nor [Muslim] Brothers, our revolution is one of the youth.”

In the course of discussions that have taken place in political salons, one could discern diverse opinions. Some people have become convinced that Islamic movements will accede to power following the fall of Assad, but only for a transitory period, during which they will be unable to solve Syria’s political problems. Those who hold this opinion are counting on these parties’ intolerance and inability to contain all of the cultural, sectarian and racial elements in society; they insist that the Islamists will inevitably fail and be succeeded by liberal, secular and leftist parties, which will rise thanks to popular support. Another opinion posits that there will be no harm done if Islamic movements assume power, and that we should give them a chance, provided they adopt the Turkish model, ie embrace a moderate interpretation of Islam which will serve democracy and achieve civism. Others think that the talk about Islamists taking over power is a form of propaganda meant to counteract democratic change.

Let us suppose that the Islamic movements were able to rule: will they simply achieve power without being subject to public scrutiny – that of the popular tide that filled the streets and the activists who have different intellectual colourings? Will they not be under the scrutiny of the various Syrian sects, which look forward to a state that preserves their religious freedoms?

Several challenges will cast a shadow over the work of Islamic parties, most important of which is whether they will able to respect cultural, ethnic, and religious diversity in Syria, and recognise the individuals’ right to citizenship, which is equivalent to freedom of belief, irrespective of its nature. This challenge needs politically mature minds, characterised by a modern view of Syrian society, and the political, social and cultural change that Syria is witnessing.

It is fair to say that, despite the fear that is disrupting the revolutionary atmosphere, we have not heard any clear calls on the part of Islamic parties to implement shari‘ah or establish an Islamic state. The members of the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood still adopt a moderate discourse as they attempt to stand with the rest of the opposition and declare their commitment to a civic state.

At the end of the day, power will not be in the hands of a single party, for it is elections that will determine who will rule the country for the next four years.

In conclusion, we should keep in mind that the revolution in Syria was not started by any political party; it was born out of Syrian suffering. As a result, no single political party or coalition is able to control the minds of others. The only guarantee for not subjecting democracy to the burden of sectarian disputes is the culture of the Syrian revolution itself, which has embraced all sects and parties and declared, in a single voice, that the Syrian people is one.