One Revolution is Not Enough

By Razan Zeitouneh

Many people don’t believe that, in the midst of the barbarism with which the regime is treating Syrians, there can still be room for emotions other than anger and pain.

Yet there are those who continue to face guns with roses. At first glance, this seems to be goodwill and kindness taken to the extreme. The rose revolutionists have a different perspective; they hope that the revolution can change more than just the regime.

The rose revolutionists have a different perspective; they hope that the revolution can change more than just the regime.

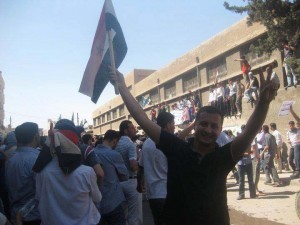

Since the beginning of the protests, the Coordination Committee of Daraya, in the Damascus suburbs, came up with the idea of holding roses in all protests, a rose for every protester. The members of that committee are among those who embrace non-violent struggle, and some of them have previous experience in this form of resistance.

They include members of a previous group known as the Daraya Youth, whose participants were arrested in 2003 after they conducted a city clean-up, distributed calendars featuring anti-bribery quotes, staged non-violent silent protests against the occupation of Iraq, and other activities that were completely unheard of in Syria at the time.

Despite that, I struggle to explain how the committee continues to convince protesters to hold roses. The issue of roses seems, on the surface, divisive and to detract from the gravity of events and the violence that surrounds them every time a protest is met with batons, live ammunition, and tear gas.

Yahya Shurbaji is one of the most prominent leaders in the town, and he says that Daraya itself is in need of roses. The revolution is an opportunity for us to change too, he says.

At first, some of the youth wanted to respond to the security forces, those whose role is to suppress protesters, with stones. The matter led to much discussion and argument.

Resilient with roses

Finally, according to Yahya, the majority of the impassioned youth became convinced that confrontation should be conducted with resilience only, not with attacks, and that movement leaders were responsible for keeping the protest on the right track so that it did not swerve toward what the regime is aiming for, whether that be civil war or counter-violence.

Yahya and his colleagues even tried to avoid using terms that imply violent struggle, such as the word “rebels” (thuwar) used in the case of Libya. Rather, they insisted on using the phrase “the youth of the revolution” (shabab al-thawra), based on the Egyptian model.

Naturally, many discussions among the youth revolved around tactical practices, such as the question of whether throwing stones and burning tires in symbolic protest would be against the non-violent character of the movement.

Despite the fact that such practices do not conflict with the non-violence of the revolution, Yahya is strongly against them. He considers them to be provocations against low-ranking soldiers, most of whom are under 20 years old and doing mandatory military service, under constant investigation by their ranking officers and in isolation from their families and home communities for several months. When these soldiers see smoke and fire, they feel that they are in a battle in which they must play a [battle] role, Yahya added.

One young man who recently served in the regime’s forces described how the situation changes into a personal matter when it involves protesters confronting the soldiers that are suppressing them. When a protester curses a soldier’s mother, for example, the soldier, who hasn’t seen his mother in months, will be provoked, and will let his anger out on the protester. In any case, throwing stones or lighting a tire does not block the bullet, nor does it prevent an arrest, Yahya pointed out.

Not all the youth are convinced of non-violence as a principle, despite their adherence to it as a practice that has characterised the Syrian revolution thus far.Many of them, rather, see non-violence as a tactic that serves the goals of the revolution. For that reason, Yahya believes that adopting a position of extreme non-violence now helps to ensure that future non-violence would be moderate, in light of the regime’s insistence on bloodshed.

What is noteworthy is the change – on a personal level – that many of the youth in the movement have reported during the past few months.

Most of the protesters in Daraya are young, and many of them use obscene language while protesting. They are easily provoked, according to their friends in the co-ordination committee. Really, who can stand up to the shabiha’s [government militia’s] taunts towards people of this conservative, religious city when they use phrases such as, “People of Daraya, where are your women?” With the help of activists on the ground in Daraya, many of the young protesters have changed noticeably.

Despite the security pressure and the fast pace of events, discussions play a large role in the city’s co-ordination committee. One goal of these discussions is to identify which practices to avoid and which to emphasise.

Yahya observes, for example, that during a wake recently held for one of the city’s martyrs, the youth were more enthusiastic about talks by activists and oppositionists about democracy and civilization than they were about ones by religious figures, who had the upper hand before the revolution.

Some youth who had once been reckless, to whom some had been ashamed to even say hello, have now become friends and partners on the path with those they formerly made to feel uncomfortable. Many of their ill-mannered and unacceptable behaviours have diminished, Yahya pointed out.

Some of the very youths who once called for throwing stones in response to attacks by security forces on protesters recently came up with the idea of offering water and roses to army and security personnel.

The idea was put into practice a few weeks ago, when huge numbers of military and security personnel surrounded the area where protests normally occur. The protesters gathered near them and started lining up water bottles and roses, attached to leaflets that said, “We are all Syrians… why are you killing us?” in the no-man’s land between the two groups.

The soldiers began releasing tear gas and shooting rubber bullets, and the protesters stepped back a few metres, and a young man named Islam took on the role of delivering the message. He came near the row of water bottles and roses, and began speaking to the security and military personnel about the peacefulness of the revolution and its goals, which include harming neither soldiers nor anyone else.

Peace Water against bullets

The soldiers were puzzled at first. Then they began collecting and reading the leaflets that the protesters had cast their way. As they did, protesters chanted, “The army and the people, hand in hand.” Then the soldiers began gathering the water bottles off the ground. One of them tried to shoot rubber bullets at the protest again, but his colleagues prevented him from doing so; indeed, they were waving at the protesters, who quietly walked away.

Yahya and his friends don’t know whether the soldiers actually drank the “peace water” that the protesters put before them. What is certain is that many of the protesters went home that day convinced that this approach could actually yield results. That day witnessed the fewest number of arrests, and no one was wounded.

The following Friday, Islam al-Dabbas insisted on crossing the dividing line and offering roses to the soldiers and security personnel directly. He aimed to achieve a kind of eye-to-eye connection between the protesters and those who had come to kill and suppress them. This is an encounter that breaks psychological barriers and allows the other side to see what the regime’s lies and propaganda prevent them from seeing.

This is usually difficult to achieve considering that orders to shoot are often timed so that soldiers fire from a distance, and hence have no interaction with the protesters except by way of weapons. Islam disappeared among the security personnel who seized him and the roses that he had sought to offer them. He remains in a cell to this day, held by the secret police.

Islam’s story in particular caught my attention, because I had believed that non-violence advocates might reconsider their approach when personal harm touched them. But Islam’s father had been arrested several weeks prior to his action, and that had not discouraged Islam from continuing the non-violent strategies he had started.

“To be killed is better than to be a killer,” Yahya said. His allegiance, at the end of the day, is to the victory of the revolution and so, in addition to the principles involved, Yahya does not see how defending oneself violently would increase the chances of the revolution’s success.

Yahya seemed like a dreamer to me, to some extent –an exception among exceptions. I do not hide the fact that I cannot look at his and his colleagues’ experience with neutrality, for I have dealt with tens of groups active on the ground from the beginning of the revolution. It is true that most of them adhere to non-violence in practice, but at the intellectual level and in many other ways, these other activists still reflect the attitudes of pre-revolution Syria.

That is the reality, and Yahya stands out in contrast: he believes that the revolution should change our perspectives on everything, on religion and society and politics. He lives his own revolution by advocating love, speaking to people’s intellect on a personal level. The revolution should be achieved inside of us before it is achieved on the ground, he says.He criticises intellectuals and oppositionists for not stepping up and offering people the new and revitalising discourses that this revolution needs.

Daraya’s experiences have influenced other towns in the Damascus suburbs. For example, on the Friday dubbed “Your silence is killing us,” protesters in Tal, inspired by Daraya’s experiment and after discussions with the Daraya activists, distributed water and date pastries (ajweh) to soldiers.

One of the co-ordinators in Daraya’s committee says that the regime, in light of its escalating suppressions and provocations, wants to drag the movement into violence, instead of properly informing security and army men about the actual facts of the protests and those who participate in them.

“We had to respond in some way or another,” this Daraya coordinator said, speaking of the Daraya experiment with water and ajweh. “We offered them water because they were thirsty at midday, and sweets because most of them were hungry, and their financial situation is too poor to buy food using their own salaries.”

About an hour after the protest started, the protesters headed to where security forces were gathered. Security personnel prepared to attack the protesters, who took the initiative by sitting on the ground in front of them.

Some of the young protesters put a row of water bottles across the width of the street. Each bottle had a piece of ajweh with a wrapper that said, “We are all Syrians…Why do you imprison us…Ramadan greetings.” Meanwhile, they spoke words of love and peace to the security and army men, through a megaphone. They said that the protest would end early today, as a gift so that the security men can get a bit of rest. Then they chanted, “The army and the people, hand in hand,” sang the national anthem, and ended the protest quietly. One of the security men collected the water bottles and ajweh, and we don’t know if they were later distributed to the soldiers or discarded.

The co-ordinator says that the experience was astonishing, especially because some of the group had greatly disapproved of the idea at first. Much discussion and arguing was needed to convince them. Indeed, some feel that members of the security forces in particular have closed their hearts to the people, so there is no use in communicating with them in any way. But experience proved otherwise, he said, for there were several situations in which security personnel helped protesters escape. Naturally, the greater the response from military and security personnel to these initiatives, the more the approach is solidified in the minds of the young protesters, the co-ordinater said.

Many may find it strange to discuss the experiences of Daraya and Tal at this particular juncture, when the regime’s violence against the people has escalated to a peak, and our lives are filled with expressions of anger and pain. But I see in these experiences a light at the end of the tunnel that will make the future less difficult than we may expect.

Some talk of love and others of change, not only in the context of this regime, but also regarding what the regime has destroyed in us throughout the decades. Some people realise that there are other things we should rebel against, whether before or after the fall of the regime. These people are not the majority but rather the exception—and a beautiful exception they are.

Razan Zeitouneh is a Syrian writer and Human Rights Activist.