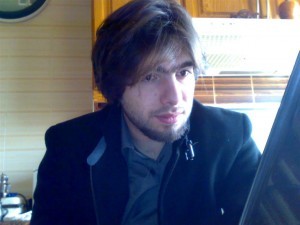

My friend, Obeida Arna’out

I can never forget that day in autumn when I met Obeida.

The bus I was taking from my university in Damascus to Aleppo made a stop in the city of Abilfida’, and among the passengers who got on was a lively and handsome young man who came and sat down next to me.

I expressed curiosity about my travelling companion, and he obliged by telling me about himself: he was from Hama, and studied architecture at al-Ittihad university in Manbij, a city in the province of Aleppo. As he spoke enthusiastically about his ambitious plans, it became clear to me that he was destined to become a brilliant architect.

Our journey together ended in Aleppo, but that was not the end of our friendship, since we exchanged contact information and agreed to stay in touch.

Obeida and I maintained an intermittent correspondence. In his final year of university, he told me he was about to finish his graduation project based on his life’s dream. He produced a unique and complex design for a Ferrari racetrack arena, and I was thrilled to know that he earned a distinction and graduated at the top of his class. That was the last direct contact I had with Obeida.

Obeida’s belief in the revolution

Obeida and I had been communicating online during his last year of university, which coincided with the start of the Syrian revolution.

I could sense a great deal of exhilaration in his words as he urged me to join the uprising. He told me of his own heroic participation in the demonstrations, how he marched at the front holding olive branches and flowers, and encouraged his friends to come as well. He would hoist children up on his shoulders as he marched through Hama, before al-‘Assi Square filled with demonstrators, and long before that treacherous bullet pierced his heart.

On the eve of what was known as the “Friday of Children’s Freedom,” I was gripped by an urge to know what was happening in Hama, the city known for its resilience, where more than 100 people had been killed that day. But the internet and all other forms of communication had been cut off in Hama, and my attempts were to no avail.

By the next day, trembling with fear, I tried unsuccessfully to reach Obeida again. I checked the names of martyrs listed on the revolution websites, and there it was: Obeida Al-Arna’out. I froze; I was simply incapable of comprehending.

I tried to think of someone who could deny or confirm the news, when I remembered that I knew a very close friend of Obeida’s. I accidently came across him online, and rushed to ask him about my friend. I begged him to tell me that the terrible news was not true, but he could not. My eyes filled with tears.

All my memories of Obeida came rushing through my mind at once.

At that moment I hated the virtual world, and regretted looking for Obeida’s friend. I considered calling Obeida’s parents, but then I was unable to think of anything to say to them. How could I ask them about Obeida’s death? How would I face his mother’s grief? Should I instead imagine his friends and family ululating in celebration of their son’s martyrdom? Or should I sense their grief shaking all of Hama?

In my confusion, I briefly imagined his parents asking me to congratulate them for their son’s new place in paradise.

Obeida was preparing to leave Syria two days after the date of his killing. He took to the streets with the other demonstrators in order to breathe in enough freedom to last him the long journey.

Obeida, just 26 at the time of his death, did leave Syria, but his departure was more painful than he had planned.