A Decade in Power, part 1: Playing a double-edged game. Syria’s International Relations under Bashar al-Assad.

It was a tough act to follow: Hafez al-Assad was known to be a savvy head of state. He was able to sustain good relations with important Arab nations like Saudi Arabia and Egypt and play on their differences. Where does Syria stand internationally ten years later, after a decade of Bashar al-Assad’s rule?

The Syrian president, Bashar al-Assad, embarked on a tour of Latin America in June, flagged as a bid to reach out to millions of descendants of Syrian and Lebanese immigrants, but it appears to have been more about finding an alternative to western support for its economic development.

Assad met his Venezuelan and Brazilian counterparts Hugo Chavez and Lula da Silva. The three shook hands, exchanged expressions of admiration and praise and took souvenir photos. The trip also took Assad to Cuba and Argentina.

It is true that Syria has managed in the past two years to pull itself out from several years of international isolation. Washington is showing more readiness to engage Syria after years of shunning it.

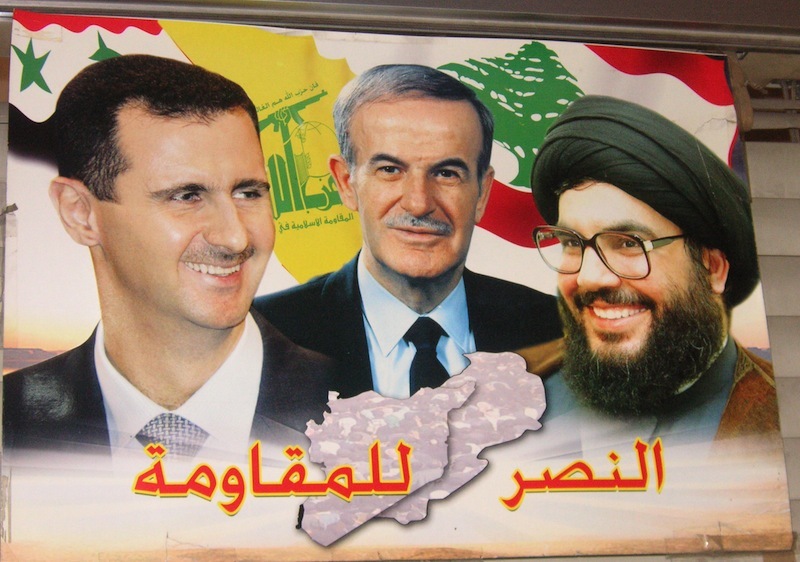

But concrete achievements on the Syrian-western front have still to be made. Meanwhile, many believe that Syria is enjoying a comfortable position today as a relevant regional power. Damascus is again playing a double-edged game, continuing to support anti-Israeli militant groups in the region and sustaining strong ties with Iran while flirting with the West economically and politically.

Meanwhile, the unresolved conflicts of the region from Iraq, to the standoff over Iran’s alleged nuclear arms program to the Israeli-Palestinian stalled peace negotiations put Damascus in a strong position to keep its regional cards close to its chest until the right moment.

What is certain according to most observers is that after ten years in power Assad has managed to prove the resilience and relevance of his regime. Syria has come a long way since he assumed power in July 2000.

Uneasy Start

But the road for the young president was not without bumps.

During the first years of Assad’s rule, Damascus gradually lost the international standing that his father was able to carve out.

Hafez Al-Assad, who was known for his shrewd diplomacy, was able to keep a balance in his relations with the West, Moscow, Iran and Arab nations during his sovereignty over the country for almost three decades.

With an expedient vision of regional and international politics, he was able to keep Syria as a relevant player in the Arab-Israeli conflict, Lebanon’s civil war, as well the Arab world’s relations with Iran.

When he died in 2000, it was clear that the international community had welcomed the transfer of power to his son, Bashar. It was first time in the Arab region that a president of a republic had passed the reins of power to his son.

Stability Better than “The Possibility of Chaos”

Back then, world leaders thought it was best to perpetuate the pragmatic legacy of the father believing that “stability was better than the possibility of chaos” in case of a regime change in the country, said a Damascus-based political analyst, who asked to remain anonymous.

Many observers had doubted, though, that the son would have the necessary political savvy to keep up with the risky policy of his father, which was all about exploiting the differences and weaknesses of neighbouring and international powers.

Also, after 2000, several factors had significantly complicated the situation in the Middle East making it more difficult for Assad, the son, to have good –or at least, neutral – relations with international and regional powers, namely, the United States and the so-called moderate Arab states, Saudi Arabia and Egypt.

Following the rise of the US as the only superpower, especially after the September 2001 attacks which led to a more aggressive American policy in the region, Damascus adopted the rhetoric of a nation resisting the hegemony of the West in the Middle East, and defending the rights of Arabs and especially Palestinians. Meanwhile, under the table, Syrian intelligence cooperated with the US security services in their “war against terror”.

But this double-edged strategy became very difficult to pursue with the invasion of Iraq by US troops in 2003 and the subsequent fall of Saddam Hussein’s Baath regime in Baghdad.

The Iraqi Menace

The regime in Damascus, for the first time since Bashar took over the leadership of the country, felt the heat of a real existential threat. The radical change in the power structure in Iraq foreshadowed the possibility of a similar change in Syria.

Damascus officially stood firmly against the occupation of Iraq. Meanwhile, the Americans pursued an aggressive policy against armed Islamist groups in Lebanon, Palestine, and Iraq hoping to change the dynamics of power in the region and to bring about a “new Middle East”.

After 2003, Washington stepped up pressure on Damascus to sever its ties with Hamas and Hezbollah and their regional backer, Iran.

Syria responded by getting more entrenched in the Iranian camp.

Some analysts said that although Syrians continued to bolster their ties with Iran as their main strategic ally in the Middle East, they were not pleased with the increasing Iranian clout in the region, which threatened their position as an essential mediator among different conflicting groups.

In Iraq, in several instances, Tehran and Damascus appeared to have different objectives with Syria supporting Sunni tribes and former Baathist elements at the expense of Shia forces.

Later, the assassination of a high-profile military commander of Hezbollah in Damascus in 2008 and later on of a Syrian officer in charge of communications with the Lebanese Islamist group in unclear circumstances reveal the uneasy nature of relations between the two states.

But other observers believe that Damascus’ strong bonds with Tehran eventually gave it more leverage at the regional level to play a future role as a mediator between the West and Iran.

Bush against the Axis of Evil

At the end of 2003, under US president Georges Bush, Congress passed the Syria Accountability Act, which imposed sanctions against Damascus for allegedly supporting terrorism and more specifically facilitating the passage of insurgents into Iraq.

Syria was also accused of trying to develop weapons of mass destruction. In 2004, Washington pushed for a United Nations Security Council resolution that indirectly called on Damascus to withdraw its troops from Lebanon, which had been stationed in the country since 1976.

Resolution 1559 also demanded the dismantlement of all militias in Lebanon, in a clear reference to Hezbollah.

The decision came as a response to Damascus’ continued meddling in Lebanese affairs. Syria refused to let go of the strategic Lebanese card, especially since Damascus had been pursuing a proxy war with Israel through Hezbollah in Lebanon, the analyst said.

Relations between Syria and the West took a more dramatic turn in 2005 with the assassination of the former Lebanese premier, Rafik Hariri. Damascus was largely blamed for his killing, an accusation that the Syrians denied.

Syria was eventually forced to withdraw its army from Lebanon a few months after Hariri’s assassination, which started the process of its international and regional isolation.

Washington recalled its ambassador from Damascus and relations soured between Syria and other Arab states, mainly Saudi Arabia, which held very close ties to Hariri.

The European Union froze an economic agreement with Damascus.

The establishment of an international inquiry to look into the killing of Hariri put Syria in an even more precarious situation. But Damascus was able to hold still.

Tide Turns

In 2006, the tide started turning in Syria’s favour. After Hezbollah was successful in resisting an Israeli attempt supported by the US to annihilate it, Damascus reaped the fruits of the military confrontation, which exposed Washington’s impotence in terms of reshuffling the distribution of power in the region.

Furthermore, the US’s unsuccessful endeavours to bring stability to Iraq gave further confidence to Syria. Meanwhile, Damascus started sending signals to the international community that it was willing to cooperate in a number of areas.

In 2007, Syria started indirect peace talks with Israel under the mediation of Turkey. Later in 2008, Syria was instrumental in allowing a deal to be made between opposing factions in Lebanon, which was on the brink of civil violence.

In return, France led the way for the Syrians to break their international isolation. The election in the US of Barack Obama, a democrat, as a president further helped Syria to regain its regional standing. Other Arab nations also followed suit in restoring relations with the Syrians.

Obama drifted from his predecessor’s policy towards Damascus by opening “channels of communication” with the Syrians. Observers said that the West was hoping to woo Syria away from its Iranian ally.

In the last two years, Damascus received a number of diplomatic, military and economic delegations from the US and the EU. Damascus hailed these signs as a proof of the world’s recognition of its importance in the region.

But some doubt that the Syrians are out of the danger zone. One analyst said that the US and Syria haven’t made any real progress in their relations yet.

The appointment of a US ambassador in Syria after a five-year hiatus has been stalled. Robert Ford, who had served in Iraq, was nominated by Washington but Congress has yet to approve that decision. Moreover, the US has extended economic sanctions against Damascus despite announcing a number of waivers on technology and aviation-related products.

Meanwhile, Syrians haven’t showed any willingness to relinquish their ties with Iran.

With Israel not apparently ready to give up the Golan Heights – a patch of land it seized from Syria in 1967- Damascus does not consider that there are any tangible incentives for it to change its attitudes in the region.

Some analysts believe that as long as the region remains in a state of turmoil and uncertainty, Syria can hold on to its regional card, mainly its leverage over Hamas and Hezbollah.

But others say that Syria cannot afford to remain tied to Iran. According to Radwan Ziade, a Syrian political analyst who currently resides in the US, the economic situation is dire because of a decline in the state’s revenues. He argued that the country’s capacity to have an effective regional role is limited because of its pressing economic needs.

He added that several factors are also keeping Damascus in check.

“At the end of the year, the results of Hariri’s international tribunal will be clearer. This would indicate whether Syria is outside the area of danger or back to it,” he said.