Displacement Crisis Worsens in Jaramana

(Jaramana, Syria) – On the bleachers of the municipal stadium in the Damascus suburb of Jaramana, families sit and wait; not to see their teams compete in a football match, but for the chance to enter their names on the aid register.

Alongside the al-Nour mosque, the stadium is one of the centres where displaced people are registered and can find shelter in Jaramana.

Both places attest to the severity of the crisis facing those displaced from their towns in the Damascus countryside, a crisis that continues to worsen as fighting between government and opposition forces persists amid an especially harsh winter.

There are now about 900,000 displaced persons in Jaramana, according to a relief worker. They are scattered between houses, schools, and half-finished buildings which alone house around 200 families.

A volunteer for the Relief Committee, a civil-society volunteer organisation working alongside the Red Crescent, explains that the crisis is far from over.

“The displacement is daily and constant, which we know from the number of new families that come to us for help,” he said, adding that most of the displaced people who arrived in November were from eastern Ghouta in Damascus.

The fighting between the army on one side, backed by the National Defence Forces and Hezbollah, and the armed opposition on the other has intensified in eastern Ghouta in recent months.

The Red Crescent volunteers working at the Jaramana municipal stadium divide up the displaced families by region of origin.

Juhayna, 52, from Ghouta, explains the aid process while waiting in line for her turn.

“It’s enough to bring one’s ID card or family registration booklet so that they can record our names and assign us a number,” she said. “After three months, the Red Crescent calls us to tell us that we’ve been granted an assistance package.”

According to Juhayna, the package comprises a food basket that contains, among other things, a sack of bulgur wheat, a sack of rice and some oil, as well as mattresses, blankets and winter clothing.

A Red Crescent volunteer who wished to remain anonymous said that there’s no way around the three-month waiting period.

“There are channels and rules we must abide by,” he explained. “All the displaced are suffering equally difficult circumstances, so we can’t help one at the expense of another.”

As for those families who fled under duress, leaving behind their identity cards, the volunteer explained that they are not eligible for aid from the Red Crescent, which requires proper identification, and they must instead go to the Relief Committee for help.

A large number of the displaced come to the relief centres to register and then return to the shelters they’ve managed to find in Jaramana and its surrounds.

The rest, around 68 families at the time of writing in early December, live in rooms that were once administrative offices at the stadium itself, rather than in tents, which despite the overcrowding helps mitigate some of the difficulties posed by rainy weather.

Umaima, 33, from Ghouta, complained about the overcrowding of what space was available at the stadium.

“There are three families in every room; the men are on one side and the women on the other,” she said.

One of the administrators of the Relief Committee explained this overcrowding, saying that sometimes unexpected waves of displaced families arrive all at once.

“Due to pressure, we’re then forced to place new families amongst the others,” he said.

On the pitch, under a small umbrella protecting him from the rain, 40-year-old Issam tries to light a fire in order to cook a meal for his family who live in one of the rooms at the stadium. They were displaced from al-Hajar al-Aswad, south of Damascus.

“We’re making lentils and bulgur today,” said Issam.

He complains of the lack of essentials for the children, such as milk and medicine.

“It’s cold, and most of the children are ill,” he said. “The overcrowding in the rooms means that illnesses are easily passed on and the colds are constant, which makes everything much more difficult.”

The displaced at the stadium have also been suffering from a lack of heating, which depends on electricity. Power cuts of at least four hours a day mean they must huddle on their mattresses under blankets for warmth.

As far as the health situation of the displaced children is concerned, a volunteer from the Relief Committee says that no cases of polio have been recorded at the centre, and that all the children have been vaccinated at the health centre in Jaramana.

“The only incidents of disease we’ve recorded have been a few cases of jaundice, which have been treated,” he said. “We have a medical vehicle especially for the centre, which distributes vaccines against any contagious diseases.”

The volunteers have been provided with vaccines from the World Health Organisation under the framework of a campaign that aims to inoculate 2.2 million Syrian children, including those living in conflict areas that were not covered by a previous campaign.

The first shipment, provided by the UN through UNICEF, arrived on November 29 and included 2 million vaccines for the Damascus area.

Providing medical aid is part of the work of the Relief Committee, which has about 60 young volunteers, most of whom come from Jaramana and had not met previously.

They communicated through social media networks and came together via their volunteer work a year-and-a-half ago, pooling their efforts in collective action, and distributing the work amongst themselves on a daily basis.

“We are part of civil society, not affiliated with any party or political body and without outside support. We have a purely humanitarian, non-profit aim and none of the young men or women who work with us are paid for what they do,” said one volunteer.

To carry out its work, the Relief Committee depends on help from the Red Crescent. It also receives donations from NGOs and families that prefer to remain anonymous, the same source said, adding that they receive no financial help from abroad.

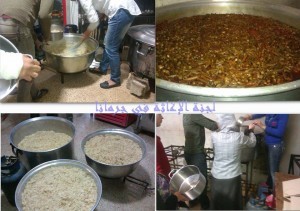

The Relief Committee workers are responsible for finding perishable foods each day, like vegetables, yogurt and meat, as well as anything donated by the Red Crescent that can be stored longer-term, like bulgur and rice, in order to prepare the daily morning and lunchtime meals distributed to the displaced families.

The volunteers have taken to calling this process “the kitchen experience.”

“Every day we cook for the families sheltering at the stadium and at the Al-Nour mosque,” said one volunteer.

Another said that despite what he sees as “a success” there is still a long way to go for the Relief Committee.

“We often have difficulties preparing the meals, either due to gas shortages, or due to a lack of ingredients,” he said. “We are forced sometimes to offer meals lacking in variety, but in any case, with all the meals we make, we try to make just the right amount, so we have no shortage and no excess.”