Darayya

By Razan Zeitouneh

On the afternoon of August 25, I was chatting online with my friend Karim, an activist who lives in a traditional Arab house – one storey, with no basement or place of shelter – in the Basatin Darayya area

Then he wrote, “A rocket has just fallen… on our neighbours’ house… Ya Allah… Ya Allah![ Oh God].” I could almost hear his cries as he wrote this.

Karim went offline, and I had to wait three days before I could speak to him again, and get his testimony about a massacre that broke our hearts – one of many such testimonies that I received.

Darayya was a star before the revolution, and a star during it. What the young men and women of the city built took an immense effort and produced an example for the future Syria of which we dream. The activism in this city never ceased to amaze us.

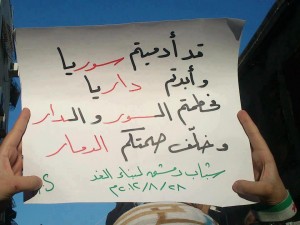

It was Darayya where peaceful protestors first offered roses and water to the regime’s troops, who repaid them by killing them without mercy. It was only in Darayya that presents for the Eid holiday were given out to the children of martyrs and shabiha alike. In Darayya, signs calling for coexistence continued to be held aloft even as the rest of the country fell into despondency after each new massacre. Other banners called for justice and fair trials, not vengeance.

Syria’s finest were planning beyond the fall of the regime and the end of the revolution. And female women activists in Darayya maintained a powerful and splendid presence.

Darayya, the symbol of peaceful civic protest, fought against militarisation of the revolution even before it became a reality. When it did come, the militarisation still did not derail the civic activism and discourse going on there.

The regime bulldozed Darayya’s fig cactus orchards a few weeks ago, destroying people’s memories and hearts along with them.

Karim told me how the attack on Darayya unfolded.

“As the shelling around us continued to intensify, I went to hide with others in my relatives’ basement. Members of the Free Syrian Army were deployed in the area where we took shelter. Regime troops and tanks were only about 200 metres away. The day ended with intense fighting and violent shelling.

“I knew by then that the regime’s army had raided the area I had fled from, including our house, and that the troops were on the move towards us. During the night, army snipers shot at anything that moved. It would have been impossible to flee, even if we had wanted to.

Shells were falling on Darayya in an insane shower. I could feel them in my heart, one by one.

“The next day, many families fled the area as the sound of shelling resumed. That went on until midday. Those who could pack up and leave did so. Some of them were hit outside the building we were in. I was left completely alone amidst the shelling and sniping.

“At that moment, I decided to go – I reasoned that I was dead either way. I got into my car amidst the smoke and rubble and headed for the city centre, which was relatively safe. During the short trip, I saw three members of the Free Syrian Army trying to hide on one neighbourhood, and six others gathered closer to the city centre. Shortly afterwards, a shell landed where they were standing. A friend told me he rushed to their aid, but found they were all dead.

“The shelling got nearer and nearer until it was about two blocks away from me. Shrapnel was flying about, glowing like hot coals. I entertained myself by waiting for them to cool down so as to collect them.

At midday, a friend of mine who’s a Free Syrian Army member came to see me. He was crying, he had abandoned his weapon and told me he couldn’t go on fighting any more. The scale of the bombardment was unimaginable, and most of his friends were killed by it. It was no longer possible to carry on resisting.

“I spent the night with friends in the area. During the night, the Free Syrian Army withdrew from the city and issued a statement saying it had done so. Regular forces were surrounding the entire city, but very few had entered it at that point.

“By the next morning, these forces had occupied one street in Darayya, where they deployed snipers.

“I then decided to flee the city together with a friend’s family, as the final offensive seemed imminent. At 7:15 in the morning, the family we had agreed to leave with arrived. Their faces were very pale.

“I asked one of them, ‘Is everything all right? What’s happened?’ He told me he had seen someone killed near the cemetery, another in his car and another on the ground. He said that anyone approaching that area was coming under heavy fire from the regime’s snipers. He showed me two bullet-holes in his car, one in the rear door and another near the fuel tank.

“At that point, we decided it would be more difficult to leave than to stay. The regime’s snipers were not allowing anyone to leave and were shooting at anything that moved.”

When our media office received information about the victims of shelling and the bodies scattered in the streets, we experienced a stunned sense of disbelief. Darayya had been our beloved daughter. If Ghiath Matar, who gave roses to regime troops, could be murdered in cold blood, then an entire city that had stood as an icon of the revolution might now be subjected to slaughter.

“We went to back where we’d come from,” Karim continued. “After a while, a friend came by and told me that four people had been publicly executed in the cemetery area. Someone else came and said that regime troops were taking men out of shelters and lining them up against the wall to shoot them. He told us to warn everyone to get out of the shelters.

“Then another friend arrived and told us that there had been a massacre in the Abu Suleiman Mosque. I just couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t believe any of the news coming in.

“Within an hour, troops arrived in the next neighbourhood, took five people out of a shelter and executed them, and then headed for a nearby square to stage a pro-regime demonstration. A Syrian state television crew arrived and filmed the event. Then the demonstrators fell silent and the sound of intense shooting returned.

“A friend came and told us that the Nammura family – the siblings, wife and children – had been executed. That’s how we spent the following day, receiving news of executions from neighbourhood after neighbourhood, not knowing when our turn would come.

“At seven the next morning, a friend came and told me we were going to the Abu Suleiman Mosque. On the way there, we could see the tragedy that had unfolded – entire houses levelled, and cars crushed by tanks with the drivers still inside.

“At a distance of 300 metres from the mosque, the smell of death was powerful. The mosque was full of bodies. We counted 123 of them. There was a 12-year-old girl, a three-year-old child and babies – all shot in the head. The babies’ heads were so soft, as if they had just skin rather than skulls, that the bullets left their faces unrecognisable.

“In the evening, regime forces returned to our neighbourhood and began breaking into shops and looting them. We were still hearing news of 20 bodies here, 30 there….”

Still in shock 24 hours after the massacre, I spoke to a young woman from Darayya.

“All that we built over a year and seven months, they destroyed in a few hours,” she said.

More than 500 martyrs and destruction on an unimaginable scale, there is no time to weep as massacres move like evil spirits from one city to the next.

The woman told me, “We will not surrender, we will not give in to death, we will rise again. Hello… this is Syria.”