Armed Zabadani breathes free air

By Razan Zaitouneh

Like most other activists who were caught unprepared by the accelerating militarisation of the revolution, Fares has always confused me: on the one hand, he enthusiastically supports the Free Syrian Army, FSA, but on the other, he has favoured revolutionary pacifism for many months on end.

In certain instances, however, it seems that Fares is facing a dilemma, especially when he talks about the recent attempt by the regular Syrian forces – blocked by the FSA – to invade Zabadani, his hometown, which lies in the countryside outside Damascus.

Fares, who holds a degree in journalism, represents the revolutionary committee of Zabadani and its surroundings in the Local Coordination Committee, LCC. He was among the first in Zabadani to take to the streets, “at a time when the educated class in my area was unfortunately still far from engaging in the revolution,” he said.

As a result of his active participation in demonstrations since their start, taking and disseminating footage of the manifestations as well as calling on people to participate in them, he became one of the most wanted opposition activists. This forced him to stay away from home for four and-a-half months in order to avoid arrest, but living in hiding did not stop him from taking part in the protests.

Today, Fares is able to sleep at home “because there is someone at the frontline protecting the city,” as he explains.

When I heard this, I thought of the dozens of families who had to flee their homes in the eastern and western parts of Al- Ghuta, near Damascus, where the FSA is present and often engages in heavy fighting with the regular forces. But I chose not to interrupt his line of thought.

“Military action started in Zabadani with people who already had weapons since they live in a rural area along the borders [with Lebanon],” Fares added. “Some of them are engaged in smuggling food products and electric appliances and they have their [own] issues with the state.”

At the start, people were wary about smugglers joining the protest movement, especially since they have contact with members of security forces, whom they usually bribe in order to carry out their work, according to Fares.

“At a later stage, the military and security campaigns led by the regime against the city intensified, and the number of detainees went over 500, in addition to the ongoing abuse and insults against people,” he said. “Some activists who were prepared to carry arms and defend civilians joined these [smugglers], and most of them do not [have any educational qualifications], and so these organised groups started to appear and became a reality.”

But this new chapter in the revolution faced several stumbling blocks at the start, according to Fares. There were many in the ranks of the armed groups who committed treason, making pacifist activists and armed militants alike an easy prey for security forces, but the situation later came increasingly under control.

At the start of September 2011, arms were used for the first time to defend demonstrators: a security patrol started shooting in the direction of a peaceful demonstration, at which point militants from the FSA fired back, forcing the security members to pull out. The demonstration then continued and the ecstasy of victory was overwhelming.

This incident encouraged civilians prepared to carry arms to join the FSA, and soldiers who sympathised with the revolution to defect, since they could find protection.

“Armed action has become a reality, and the pacifist movement cannot override it,” said Fares. “These [people] carried arms in order to defend themselves at the start, and then to defend us once their numbers increased.”

The defining moment was the day when the “strike of dignity” began; armed militants promised shop owners they would protect their property if security forces tried to break the strike, and they honoured their promise.

The militants were expecting an incursion into Zabadani and began preparing themselves to confront it two weeks before it happened, according to Fares. They raised earth barricades at the four entry points to the city and planted bombs along the roads that military vehicles were expected to take. The scarcity of military resources available to the FSA militants forced them to rely on very crude yet readily accessible material in order to make these bombs.

But the difficult circumstances did not deter Zabadani’s armed militants from engaging in the confrontation.

“Some stayed on the frontline for five days on end in temperatures of minus 8 [degrees centigrade] and their frozen fingers failed them when they tried to pull the trigger,” said Fares.

The FSA survived the battle and inflicted heavy losses upon Assad’s forces, according to the inhabitants of Zabadani, which forced them to withdraw from the city and gave the rebel fighters a big morale boost because they gained greater public support.

“[The FSA is not receiving] any support for armament; I came across militants one of whom had only four bullets that he wanted to use to defend his neighborhood and then run away or die,” said Fares. “But this army enjoys the support of the people and [its members] are present in their own area that they know like the back of their hand; they are defending [their] homeland and dignity, and they have faith, whereas the regime’s army is being eaten up by fear and is defending one person. Many of [its soldiers] sympathise with the revolution, and some wouldn’t even aim [their fire] at the city,” said Fares.

But he acknowledges that the regular forces are capable of raiding the city with all the “force and brutality” they possess, and also realises the complications of militarisation in the long run. But in his view, military action against the regime is now a “reality” that must be dealt with.

The militant journalist believes that the way the FSA is presented has an important bearing on its actual performance on the ground.

“The more positive the image we give of the FSA… the more it will reflect its members’ conduct; [the same applies] to the parallel civil action,” said Fares.

I did not ask Fares about the nature of the “parallel civil action” required; we all know that the regime’s increasing brutality has muffled all voices other than the ones calling for militarisation.

But despite his fervent support for the revolution, Fares still manages to be critical of the political changes his city has witnessed. He has a few reasons not to hold the local council that was recently formed in Zabadani in high esteem, one of which is that it was tailored by individuals and was not the result of collective action.

Nonetheless, Zabadani has done a better job than most other areas in showing solidarity between civilians and armed militants in order to manage daily life, while the threat of invasion is still imminent, according to Fares.

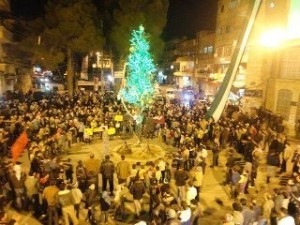

Zabdani is indeed worthy of praise. One of the banners that Fares and his comrades recently hoisted to salute Aleppo reads “Oh Aleppo… glory befits you”. A similar tribute applies to Zabadani too. Oh Zabadani… freedom befits you.