Syrian Regime Takes Aim at Opposition Employees

Salem Nassif

(Damascus, Syria) – The Syrian regime has retaliated against many public employees who support the opposition by dismissing them from their jobs following their arrest. This is taking place in violation of Syria’s labour law governing state employees, which only allows for the termination of employment as punishment in specific cases, and then only with the approval of the prime minister.

Moreover, legal experts say these decisions appear to be made without going through the courts. Instead, the security branch issues a directive, which is delivered to the governor who in turn sends it on to the relevant administrative branch for execution. More often than not, the pretext for terminating the staff’s employment is that they took an “unexcused leave of absence” of 15 days or more – often the period of their incarceration.

Nasser, 57, a lawyer, holds the administrative organs of the state accountable for violating “even the [weak legal protections] set out in Law 50, the labour law passed in 2004 which deprives the employee of the right to challenge his or her dismissal.”

Moreover, he said the Law of Demonstration, which was issued in April 2011 and labels any non-state-approved protest as a “riot,” does not include any article saying that an employee who breaks the law should be dismissed from his or her job.

“The problem is that administrative authorities are…being used as a tool by the security forces,” said Nasser. “I have encountered many cases in which even the governor does not dare allow an employee to return to work, despite receiving a justification for [the employee’s] absence. The decision lies with the security branch. Even the judge, when consulted, is in a weak position.”

The public sector is the largest labour market for Syrians, supporting countless families. According to official statistics, in 2010, the number of state employees exceeded 1 million, and that number excludes military and security personnel.

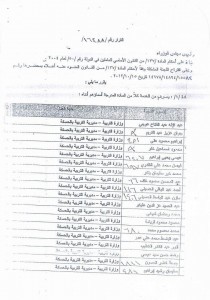

Traditionally, any government decision to lay off employees would be published in the official newspapers, but since the beginning of the revolution, only one such decree has been published. On November 18, 2012 Prime Minister Wael al-Halqi issued a decision to fire 90 employees, most of them teachers and supporters of the opposition who had been summoned or arrested by the security services.

Most firings take place far from the media spotlight, as internal directives are seen only by the relevant departments.

The issue of unlawful firings has not received the attention it deserves, except for a few statements denouncing the practice. There have been no serious attempts to document the phenomenon in an organized way, apart from a few individual initiatives to track the cases by region, such as in Idlib and Aleppo.

Human Rights groups have not concerned themselves with this issue, and even the opposition factions have not addressed it or tried to find a solution by demanding due compensation for affected employees.

Yara, 31, an activist working to document arrests, pointed out that most activists and rights groups are preoccupied with trying to document the dead and the displaced. She added that in cases of unlawful dismissal, it can be difficult to know whether someone was fired as a result of their arrest or chose to leave his or her job voluntarily as a form of protest against the government.

“The threat of dismissal is one of the most powerful weapons used by the regime to undermine the opposition and the revolution by putting many Syrians in real trouble, since it’s not the employee alone who pays the price but his or her entire family as well,” said Yara.

Hadi, 33, is one such case. Hadi was working as an agricultural engineer for the government before he was fired. His five-member family were dependent on his monthly salary of 18,000 Syrian Pounds (about $90), a quarter of which already went to pay off a loan he took out before the revolution from a state-owned bank.

Hadi was arrested for his political activities, and despite the fact that he was released in early April following the general amnesty decree, he was suspended without pay. Upon further investigation, he found that he needed the approval of the security branch before he could resume his position – an approval that has so far not come through.

After Hadi’s firing, his family had no source of income apart from 6,000 Syrian Pounds (about $30) they collected in rent from a small apartment they owned. Like many Syrian families, they were forced to sell what they could of their gold just to survive. Today, Hadi is looking to leave the country, since his chances of finding a job in Syria are slim, but he fears his arrest means he is banned from travelling.

Hadi’s is just one of many such stories, stories of hardship that mirror what is happening in Syria on a wider scale.

Kamal’s story began with his arrest in June 2012 following his participation in a peaceful protest. Upon his arrest, the 47-year-old said the head of the security branch turned to him and said: “You are a peaceful supporter of the opposition, I can tell, but remember: In Syria there is no opposition, there are only terrorists and loyalists.”

Kamal was surprised when, after his release, he was transferred to one of the directorates that fall under the ministry he worked for and where he was obliged to work under the rules of the scholarship he had gotten to do his graduate studies, which also prevented him from practicing any other profession or resigning.

“I entered the new headquarters and found several people who had been transferred like me. One of them welcomed me, saying: ‘you are the new doctor? Now we’re 11, but they said you will be working in the clinic.’ I replied: ‘Yes, I was just transferred, but I’m not a doctor of medicine, I have a PhD in engineering!’”

Kamal spent nearly a month in his new job, drinking coffee and tea while awaiting the end of his “imprisonment shift,” as he called it, at 3:30 PM, so he could go home.

Shortly after Kamal’s salary was eliminated and he was told he was suspended from work. Since that time, Kamal jokes that his only job is that of “political storyteller.”