A Sign from Deir El-Zor

Ward al-Assi

“Here lies the Deir of Hearts: Angels carry the sorrow of Syria.”

This sentence, written on one of many Facebook pages dedicated to the Syrian revolution, caught my attention a few days ago while I was looking for news of my home city of Deir El-Zor. My curiosity pushed me to seek out the young activists behind the page, called Kartouna min Deir El-Zor (A Sign from Deir El-Zor).

The page features a collection of cardboard signs painted black with white lettering that said things like “What is happening is not a crisis… it’s been happening for 40 years” and “Oh glorious Kafranbil, your banners downed their planes”.

The young men and women of Kartouna say they are dedicated to defending their city and their love of freedom. They chose the colours black and white because they evoke the schoolyard aesthetic of blackboard and chalk.

“Black is usually the colour of sadness but despite that we made it a space for imagination, love and joy,” one of the activists told me. “We started the page to lift, even just a little, the darkness that has descended on this marginalized city.”

The youth of Deir El-Zor say their city has suffered from neglect since long before the outbreak of the revolution and it continues to be marginalized by the Syrian National Council and many other international players. There are almost no news reports about Deir El-Zor compared to other Syrian cities, despite continued efforts by activists to send videos and news daily.

I got in touch with the administrators of the page and asked them about my city and its people, and about my family and my friends who are still there. I was told that “the city is completely destroyed, but we’re not leaving.”

The activists of Kartouna are all civilians; they have never carried weapons despite the constant shelling and the siege that has been strangling the city since in mid-June last summer.

“Everything is destroyed–the maqabi market, the schools, the shops, the main and side streets, the personal status registry, the Baath party headquarters, mosques, police stations and tens of thousands of homes,” says Kareem, one of the activists who works on the page. “There are just a few buildings in a few neighbourhoods that have not been destroyed, and that is where the few thousand residents left take refuge.”

The administrators of Kartouna are young people from the heart of the city who want to protect it through their signs and volunteer work. They are a group comprised of 16 activists living in the city, with more than 31 others who have left Deir El-Zor but continue to work with those on the ground to provide aid.

“Our lives are virtually non-existent; we don’t get to perform our normal activities as civilians,” said Ruba, one of the founders of Kartouna. “All we do is distribute medical supplies and aid, visit the wounded, teach some of the children and play with them if we can.”

The volunteers of Kartouna are also working on documenting the remaining families of the besieged city, who do not number more than 640.

“During the rare periods of calm we go around with cameras and papers,” says Ruba.

The goal behind this documentation project is to create a database to assist activists in supplying the population with aid and ensuring their safety.

“We are not heroes or role models,” says Ruba. “We work because we have faith in a better future, even if we will not live to see it, others will.”

Abdel Nasser, another activist, remembers some of his fellow volunteers who were killed in the line of duty.

“One of our dearest friends and Kartouna volunteers was martyred by mortar shrapnel while covering one of the affected areas. He and some other civilians from the neighbourhood were killed,” he says. “Another young man who volunteered with us also died–he was shot by a sniper in the Jabeela quarter.”

There are seven people responsible for writing the slogans and designing the signs.

“We don’t rely on techniques in our work; rather insist on staying true to its nature,” says one of the Kartouna activists. “We write by hand and without expensive materials, just chalk. We choose our phrases carefully and after consulting each other. We avoid any religious, sectarian or militaristic slogans and write our signs based on what is happening in Syria. Our signs are a revolutionary act, and we know they are part of a series of such acts.”

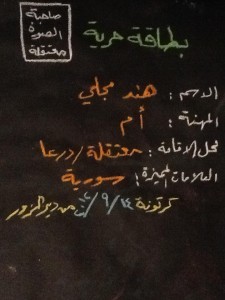

Recent signs include one titled ‘Freedom Card’ a play on ‘identity card’, which listed the names of Syrian detainees. Another, titled ‘New Syrian Traffic Signs’ uses the language of traffic signs to make a statement about the importance of combating sectarianism and respecting the rights and beliefs of others.

“We reject sectarianism and are absolutely convinced that the regime is fuelling these ideas and trying to spread them among the public,” says one of the activists in charge of writing signs.

“Before the siege, we held hundreds of signs in the street,” says Walid, another activist. “Today, we are still committed to raising them, even in rooms and other closed places, and of course online.”