“No Compulsion in Religion:” Revolution Anniversary Commemorations Cause Controversy

Hazzaa Adnan al-Hazzaa

(Kfar Nabel, Syria)—Kfar Nabel resident Hassan al-Ahmad, 27, once a student at Aleppo University’s Faculty of Economics, put his studies on hold and joined the Syrian uprising in its second week, becoming one of its most outspoken activists through his work in the media, and also going on to head the organization “Aish,” which rejuvenates walls and structures through murals, paintings and graffiti.

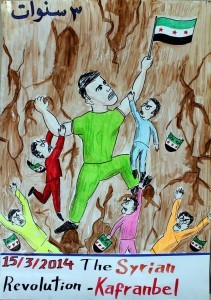

During the Kfar Nabel demonstration on March 15, 2014, commemorating the third anniversary of the revolution, Ahmad chanted its very first slogans, including “God, Syria and freedom only,” and “the Syrian people are one,” echoed by a crowd of barely one hundred people, about a quarter of whom were activists from outside opposition-controlled Kfar Nabel, which has a population of about 30,000.

“We chanted those slogans through the belief that the goals of the revolution, those of freedom, justice, equality and democracy, are the absolute bottom line,” said Ahmad. “And everyone, of every colour and every stripe, should be able to agree on that.”

In addition to those refrains, the activists hung banners on Kfar Nabel’s walls and carried dozens of posters and placards that read: “No Compulsion in Religion.” Derived from the Quran, the slogan, as well as its other variations, did not sit well with everyone in Kfar Nabel.

According to Amer Matar from Raqqa, head of the Street Alliance for Media and Development, the activists’ selection of a quote from the Quran is part of an ideological battle with Islamic extremists from all factions.

“We want to fight ideas with ideas,” he said, “confronting them with words from the Quran and sayings from the prophet, peace be upon him.” Matar believes that challenging ideas with other ideas is a stronger strategy than taking up arms against them, and he is confident of victory in such a battle since he believes that Islam is based on freedom of belief and worship and on religious tolerance, as represented by this text in the Quran, which reads: “Invite [non-Muslims] to the way of your Lord with wisdom and good instruction, and argue with them in a way that is best.”

Hassan al-Ahmad agrees with this point of view. He has had personal experience with Islamic extremism: he was tracked by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria’s (ISIS) intelligence bureau when they took control of Kfar Nabel during the last week of 2013. He was forced to go underground because of his activism and because of his murals, which publicly demand freedom for all. Ahmad believes that Islamic extremism is still present in Kfar Nabel, even after ISIS was ousted in early 2014.

“Every time we paint a mural slogan demanding freedom, such as ‘Freedom First,’ we see it wiped off the next day, with another slogan painted over it, such as ‘We Demand an Islamic Caliphate,’ or ‘Down with Secularism,’ or ‘No Civil State,’” said Ahmad.

Despite the fact that “No Compulsion in Religion” is taken straight from the Quran, Abdallah al-Saada, 40, a sheikh close the Islamic Front, protests the “inaccurate use of the verse,” as he puts it. Saada explains that the verse actually means that, “Muslims cannot force members of other religions or atheists to convert to Islam, but Muslims themselves must conform to the religion’s teachings, and can in fact be forced to do so in some cases, such as when forcing women to wear the veil.”

The Kfar Nabel demonstration was part of the tradition of “street celebration” commemorating the revolution. Held in Damascus province on the revolution’s first anniversary and in Raqqa and Aleppo province on its second, activists wanted to hold the commemorations for the third anniversary in Idlib province, which is almost entirely free of both regime and ISIS control. In addition to the protest, the commemoration encompassed other activities held over five days between March 14-18, 2014, and which included mural painting, theatrical performances held in different parts of Idlib, an afforestation program in Maarat Misreen, and an exhibition on the effects of the war in Saraqeb.

Kfar Nabel was chosen as the site for the protest because it has served as “the compass of the Syrian revolution,” according to documentary filmmaker Abdallah Hakawati, who is from Aleppo, and because “it is the voice through which the Syrian revolution speaks to the world,” according to Amer Matar.

Hakawati and Matar upheld these ideas throughout the demonstration in Kfar Nabel without ever leaning toward any political or military faction, instead addressing their banners and drawings to all the people of the world. One of these banners was the one commemorating the Boston bombings of April 15, 2013. Written in English, it read: “Boston bombings represent a sorrowful scene of what happens every day in Syria. Do accept our condolences.”

Grocer Qassem al-Qassem, 45, accuses the activists of “trading in blood, coming to Kfar Nabel to take photos and make money at the expense of all the afflicted population.”

Matar counters these accusations by pointing out that the activists have funded the celebration out of their own pockets and are gaining no financial returns from it. He also emphasized that his organization (the Street Alliance for Media and Development) is non-profit; its only goal is broadcasting the Syrian reality to those in the rest of the world, raising awareness and helping those displaced and affected by the conflict.

An artist residing in Germany and originally from Deir al-Zor, Hiba al-Ansari, who also works with the organization, asserts the same thing. Ansari chose to exhibit her work in an abandoned house adjacent to the demonstration site, where a bombing by the regime air force on August 28, 2012, killed 32 people, among them women and children. Entitled “Barzakh,” (Isthmus), and running alongside the anniversary celebrations, the piece consists of an installation: 38 sheep legs, bought from the market, each pair dressed in child’s clothing and strung up on five ropes inside the house, which was almost completely levelled. This raised the ire of Sheikh Abdallah al-Saada, after one of the relatives of the dead complained to him. “This is not morally acceptable,and it hurts the feelings of those related to the victims,” he said.

Ansari actually agrees with Sheikh Abdallah al-Saada, but the piece was planned deliberately in order to get across the message that “Bashsar al-Assad is slaughtering us like sheep. The remains of our carcasses in the debris of our destroyed homes have become a regular sight.” Ansari maintains that her work was “inspired by painful reality of our sufferings, and is not an ode to paganism,” as some have accused it of being.

A military aircraft crossed the sky above Kfar Nabel minutes before the demonstration was set to begin. Many said that this discouraged dozens of other attendees from taking part, as the demonstration square has been bombed by the military on four occasions since the armed opposition seized control of Kfar Nabel in August 2012. Ahmad al-Issa, 39, an activist in the Kfar Nabel volunteer organization “Union of Revolutionary Bureaus,” believes that the small number of protesters is due to the perceived futility of demonstrations these days. “The time for demonstration is over!” he said. “The only thing that works anymore is armed combat.”

But Hassan al-Ahmad still believes that protests and demonstrations have a central role to play, because “they express the fact that there is immense anger over injustice and tyranny.” He also believes that the opposition took up arms in the first place “in order to safeguard the peaceful nature of the revolution.”

Notably absent from the demonstration was Raed al-Fares, head of the media office in Kfar Nabel and author of the Boston bombing banner as well as a number of other banners besides. Fares is still completing medical treatment outside Syria on his arm, after he was shot in an assassination attempt on the night of January 29, 2014, as he made his way home from the office.

The same aircraft, or another one, flew once more above Kfar Nabel during the demonstration, and the protesters scattered to shouts of, “They’re going to bomb the square!”