Consumer Fraud Leads to Deaths in Qamishli

By Vyan Mohammad

(Qamishli, Syria) – A day after Seebar didn’t show up for work, his colleagues learned of his death at the Qamishli National Hospital. According to his friend and colleague Housheen, Seebar had suffered from an upset stomach, nausea and severe headaches.

Doctors diagnosed Seebar with alcohol poisoning. According to Dr. Aras Abdel Aziz, the symptoms of alcohol poisoning appear between 24 to 48 hours after the consumption of a drink with a high percentage of methanol. Those affected may lose their eyesight and suffer from kidney failure, after which all bodily functions fail.

In September, a batch of alcohol killed 11 people over a few days in September 2013 in Qamishli. Omar al-Akoub, the director of the National Hospital, said the alcoholic beverages the individuals had drunk contained a high percentage of methanol.

Methanol is a poisonous, clear liquid with a smell that resembles ethanol. While ethanol is used both as medical grade alcohol and as the main ingredient in alcoholic drinks, methanol is usually found only in trace amounts in alcoholic drinks. A high percentage of methanol is more likely to be found in adulterated alcoholic beverages, which puts consumers at risk.

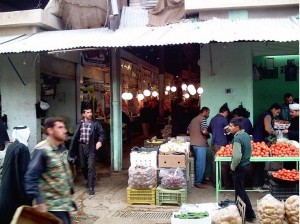

Alcohol is sold openly in Qamishli in a number of shops with state-issued licenses, particularly in the Christian majority Wihda Street. Abu Azou’s Mini Market is one such example. It sells food items, household cleaning supplies, chocolate, snacks, and imported as well as locally made alcohol among other things.

“The price of alcohol has skyrocketed in the past few months,” Abu Azou said. “A case of Turkish beer imported through Iraq used to cost 4,000 Syrian liras (28 dollars), and now it costs 8,000 liras (56 dollars) liras. This is because of the rise in shipping costs. A bottle of Aleppo-made Sharq Beer used to sell for 35 liras(.25 dollar), but now it’s 150 (1.00 dollar).”

This price increase led some in Qamishli to produce alcoholic drinks such as whiskey, arak and wine in their homes and sell them to shops.

The alcohol poisoning deaths came just after a food poisoning outbreak that affected 14 children. Doctors initially thought they may have cholera, but upon further examination, it appeared that all of them had consumed a batch of contaminated chicken imported from Turkey, according to Dr. Ali Eliad from the Kurdish Health Council in Qamishli.

These incidents of poisoning appear at a time when Qamishli is experiencing a severe food shortage due to the difficulties in transporting goods into the city. Armed men at checkpoints on the roads leading into the city often confiscate goods or demand a commission. Their political affiliation is often difficult to determine. Merchants are sometimes forced to pay a commission on their sales to bandits, so the goods are sold for even higher prices. Imported goods usually go through the Simalka border crossing with Iraqi Kurdistan, which falls under the control of the Supreme Kurdish Council.

Qamishli’s markets are filled with products such as infant formula, oils, fats, cleaning supplies, and even chocolate, biscuits and frozen meat. They come from a variety of countries such as Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and others.

Local and foreign food products sold in shops or stalls in the city are not subject to any inspections that certify their fitness for consumption. The Institute for Supplies in Qamishli used to perform this function before the uprising began in March 2011 through periodic inspections at shops, restaurants and bakeries to ascertain the quality of the products and their compliance with the prices set by the state.

The Supply Department, run by the provincial government of Hasaka, and local council are now responsible for these inspections in the city. A Damascus Bureau correspondent asked the department’s employees about the reason for the neglect, but she received no answer. A source told her the employees had been told not to work by the central government in Damascus.

Administratively, both the Supply Department and the Institute for Supplies are still controlled by the Damascus government headed by President Bashar al-Assad.

The Kurdish Medical Council, which is part of the local council dominated by the Kurdish Democratic Union Party, lacks experience and expertise. Dr. Ali Elias, a member of the Medical Council, says that they have no specialized labs to conduct necessary tests for samples they take from food items. However, they sometimes send some samples to Turkey for testing, as they did with the frozen meat imported from there. Upon receiving the results, the Medical Council released a statement declaring the meat not fit for consumption because it had gone bad during transportation and storage. The Supreme Kurdish Council’s police force, the Asayesh, shut down some of the market stalls that were selling any suspected meat from the same distributor.

The food poisoning spread panic in Qamishli, and eventually led civil society groups to launch consumer protection initiatives.

“After we saw food, and especially meat, being sold on the street uncovered and unrefrigerated, and no inspections, we formed committees of veterinarians and volunteers to test the meat and canned goods coming in from Turkey,” said veterinarian Aslan Hasou, a member of Rouj, an environmental organization. “We found that they were unfit for human consumption.”

According to Hasou’s sources, the trucks used to transport chicken are often not refrigerated and sometimes have to wait for several days at the border before being allowed entry into Syria.

Hasou says attempts to coordinate between environmental organization Rouj and the Supply Department to restart regular food inspections failed since the department did not engage with him.

There were no legal ramifications for the cases of alcohol poisoning that led to the deaths of 11 people in Qamishli. Ahmad Darwish, a member of the general administration of the Kurdish security force, the Asayesh, in Qamishli, said that not a single family member of the Muslim victims’ families filed a complaint or pressed charges.

“Who would dare say that his son died from a swig of alcohol!” he said.

After the statements made by doctors of the National Hospital that cases of methanol poisoning were traced back to alcohol manufactured in Qamishli, Asayesh units interrogated several individuals known to produce alcohol locally. Large amounts of adulterated alcohol were found in their warehouses and destroyed. However, no case was brought against them and no decision was issued banning the local production of alcohol.

Currently, locally made alcohol has disappeared off the shelves of even licensed shops in Qamishli. Abu Azou, the mini market owner, attributes this to the alcohol poisoning deaths.