The Boy Who Died Feeding His Cat

In February 2014, while I was doing humanitarian relief work in Harasta, I decided to open a charity kitchen to serve food to those in need.

As premises for my project, I chose a small farmhouse. There I met Abu Steif, the caretaker, a kindly 40-year-old whose gentle nature had not been hardened by war.

Abu Steif’s seven year-old son Mohammed would sometimes accompany his father to work. He was a friendly boy, sweet as an angel. I grew to love Mohammed, and unknown to me, he came to love me too.

Friday, April 24, 2015, began the same way as any other day. We prepared food for the families of Harasta’s martyrs and packed it into our minivan for dispatch. Mohammed helped us with the packing, running back and forth between the kitchen and the van. He was happy and proud to have been entrusted with the job.

I drove off to deliver the goods, and was barely gone two hours, but when I returned, I was met with devastating news. There was a pool of blood outside the farmhouse, and Abu Steif sat next to it weeping.

He told me he had been indoors when he heard an explosion. He ran out to get Mohammed, only to find him lying on the ground covered in blood.

I asked Abu Steif to get into the van and we drove off towards the Harasta medical centre, where the ambulance had taken Mohammed. But he wasn’t there. His injuries were so severe that they transferred him to Douma.

When we reached the Douma hospital, we were told that Mohammed was undergoing an operation. Two hours later, they came out and told us that Mohammed was in critical condition. Both legs and both hands had been amputated and he had been blinded in both eyes.

We left Mohammad hooked up to a life-support machine and headed back to Abu Steif’s home. He was on the verge of a breakdown, but he needed to tell his wife the news. He did so as gently as possible, omitting the heartrending details of Mohammed’s injuries.

Mohammed’s mother insisted on going to her son’s bedside, but Abu Steif wouldn’t permit her to, as he wanted to spare her the misery of seeing her son in that condition. He told her that night-time visits were not allowed at the hospital.

The following day was an extremely difficult one to face. It was clear that Mohammed’s injuries were too severe for his small body to overcome. We knew his life was ebbing away.

Three days later, the little angel Mohammed succumbed to his wounds and passed away.

It later emerged that he was feeding a stray cat he had adopted when a shell fell nearby. The shrapnel hit both Mohammed and his cat. Only the cat survived.

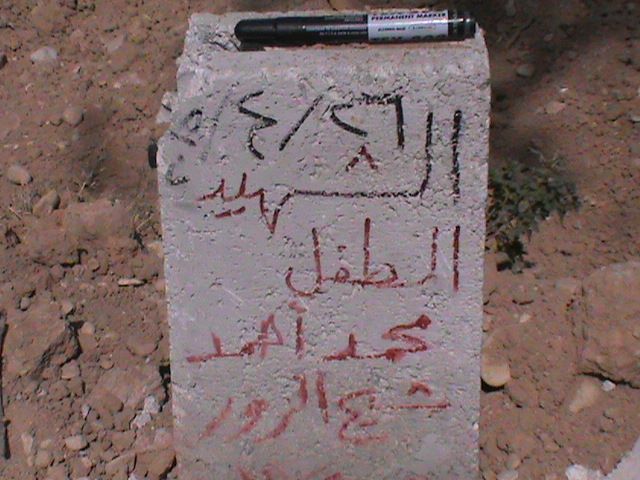

Mohammed was buried in Harasta without his mother seeing him. We decided this was for the best, as she would never have been able to forget the sight of his grievously wounded body.

When I visited Mohammed’s grave, I found a small bunch of flowers attached to a note written by one of his friends. “Love you for ever, your friend Bilal Najib”.

The sadness I felt was so overwhelming that I couldn’t face visiting his family to offer my condolences until three days later. When Mohammed’s mother saw me, she hugged me and wept. She told me how much her little boy had loved me and how he had kept asking for permission to visit me with his father.

Her words left me feeling nothing but guilt. How I wish he had never loved me or visited me. His life might have been spared.

Some people say that those of us besieged in Eastern Ghouta have grown accustomed to death, but that is not true. Each person we lose is irreplaceable, and each death leaves a lasting sad memory in our hearts.

One day, our salvation will come, but our joy will be incomplete because those with whom we wished to celebrate are no longer alive. The sorrow of loss will forever be our companion, no matter how much we try to ignore or hide it. Some wounds never heal, especially those inflicted on the soul.

Faten Samih Abu Fares is the pseudonym of a Damascus Bureau contributor living in Eastern Ghouta, Syria.