Regime supporters and opposition united in rejection of general amnesty

Note: The editorial team has changed the names of the speakers and withheld the identity of the author for their own safety.

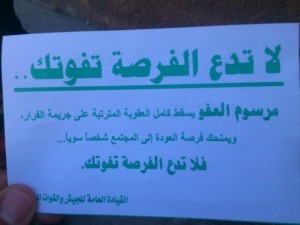

Since the start of the revolutionary movement in Syria, President Bashar al-Assad has issued several general amnesty decrees in an attempt to contain the instability and preserve the regime. In the past, regime supporters have accepted and justified these decrees, as they do with all regime decisions, while the opposition, as usual, rejects any decisions taken by Assad.

However, the most recent amnesty decree, issued by Assad on April 19, 2013, which grants a general amnesty for crimes committed before April 16, 2013, has united supporters of the regime and the opposition on at least one issue: Both sides have rejected the amnesty outright, albeit for different reasons.

“The regime issued the amnesty for two reasons: First, it is trying to ease the general political pressure on it over the issue of political prisoners,” said Kifah, 31, an opposition activist. “Secondly, the regime uses these decrees to win popular support, and to convince the international community that it is seeking a political solution, so it brandishes the amnesty in the media to prove it.”

Kifah does not believe that the latest decree differs in essence from earlier such decrees, which she rejected in form and substance.

“[Following the other decrees], the regime did not release any political prisoners or peaceful activists, as evidenced by the continued detention of people like Mazen Darwish, Eyad Sharbaji, Abdul Aziz al Kheir, Rami Henawi and others,” she complained.

Ahmed, 61, a retired bureaucrat, also rejects the decree, but as a supporter of the regime.

“I do not think that continuing to issue amnesty decrees will change anything,” he said. “We’ve tried that more than once, and each time it just released more criminals who returned to committing more crimes and acts of vandalism, causing more security tension in the country. This makes things worse, especially during a crisis.”

Even before the April 19 amnesty was issued and the pro-regime street became more vocal in its dissatisfaction, many were suffering as a result of the unrest and the deterioration in security. They could no longer stand by while the regime pardoned those who had committed crimes against innocent people.

“Criminals should be punished, and pardons are not appropriate during these difficult times,” said Hanaa, a 42-year-old housewife and a resident of Damascus. “What sin have we committed that bad people are pardoned to come back to harm us and our children?”

Hanaa was deeply resentful of the amnesty decree, especially since it included a criminal who threatened her son.

“In our neighbourhood there was a drug addict, a thug who hit my son, a university student, and [tried] to rob him. We did not file charges against him because he and his family have a bad reputation and could harm us,” she recalled.

“We were delighted when he and one of his brothers were finally arrested on charges of drug use, and we were shocked when he was released following the decree. I felt a sense of injustice and oppression when he was released. I do not understand politics, but I am sure that releasing criminals is a grave mistake that is repeated with every amnesty,” she said.

Mahmoud, 34, a lawyer, questioned the constitutionality of the amnesty, pointing out that according to article 75 of paragraph 7 of the new constitution, the power to grant a general amnesty is reserved for parliament, while the president only enjoys the power to grant individual pardons.

The constitution gives the president the right to legislate according to article 113 of paragraph 1, which states: “The President of the Republic retains the power to legislate outside parliamentary sessions, or during the session if absolutely necessary, or when parliament is dissolved.”

Mahmoud takes issue with the vagueness of the phrase “if absolutely necessary,” asking: “What is so absolutely necessary that it required the adoption of four amnesty decrees by the president within two years?”

Mahmoud said the parliament could have approved a general amnesty during its sessions rather than the president taking unilateral decisions, in contravention of the constitution.

Zainab, 36, who is also a lawyer, added that the decrees include many loopholes.

“The amnesty did not include so-called crimes of terrorism, which are tried before an anti-terrorism court,” explained Zainab. “The only crimes covered by the amnesty are those referred to the judiciary according to [conventional legal channels], either by cases filed directly, or through the public prosecutor, or a complaint. The dangerous aspect is that those who are tried for terrorism are referred by the security branches, who have no connection to the judiciary and who can refer anyone based on a variety of prefabricated accusations, to an exceptional anti-terrorism court.”

Often, she said, a suspect remains in custody secretly until the case reaches the court, where it can take several months to resolve, only to see the defendant acquitted of charges.

Syrian Minister of Justice Najm Hamad Ahmad explained in a statement that “the decree excluded a very limited number of crimes, including crimes of treason, espionage and terrorism.”

The regime usually uses the word “terrorism” to refer to the activities of the armed opposition.

Nermine, 29, a journalist, said the regime has no credibility when it comes to implementing these decrees.

“All they’re doing is releasing petty criminals who committed theft, looting, swindling and fraud, while those who hold oppositional political opinions are not included, or if a few of them are, it is on the principle of distinguishing between different [types of cucumbers],” she said, referring to the common proverb used to describe unfair discrimination between two categories of people. “Implementing amnesty comes down to bribes and mediation to get a detainee released.”

In Nermine’s view, amnesty decrees are not enough to restore trust between the government and the people.

“If the government wishes to the restore trust of the people through these decrees, it must disclose the names [of detainees] rather than allowing the process to be exploited by influential people who flout the law and the decrees.”